My notes on processing nanopore data

In this post, I document the Azolla lab protocol for nanopore DNA metagenomics sequencing. It should be updated kind-of-regularly when applicable, and may be used by future Azolla lab members or anyone else interested in starting nanopore sequencing.

DNA extraction

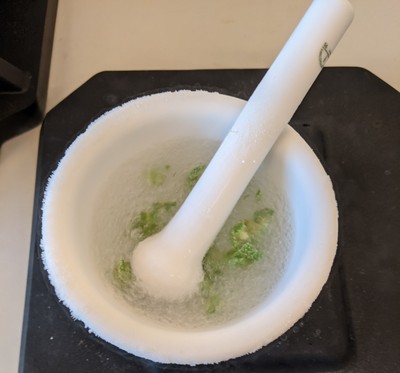

For DNA extraction of Azolla ferns I use a protocol from nanopore itself: “High molecular weight gDNA extracted from fever tree leaves (Cinchona pubescens)”. I don’t think I can post this protocol here online, but this talk and this preprint should already be very informative. The protocol itself can be downloaded from the nanopore community website here. Naturally, use only the best and healthiest plant material you can find to start this protocol The only main modification I made is grinding the plants while submerged in liquid nitrogen, rather than having a mortar in an ice bucket. This warrants extra care though when moving the ground plant powder to the Carlson lysis buffer. If any liquid nitrogen remains in the Carlson buffer, this will explosivelly evaporate in the warm buffer.

Nanopore sequencing

Before starting a library prep, I always do a quick hardware check of the mininon device in the minknow software. Then, after using the high throughput library kit, prep you library and crack open your fresh flowcell. We often re-use flowcells, but I always do a flowcell check before sequencing. In the past I have forgotton to do this before priming the flowcell and loading it. It seemingly still works, but the flowcell check should be done with the storage fluid loaded still.

In setting up your sequencing settings, I recommend to skip basecalling given our specific hardware. Fast basecalling on CPU works if you really want that information directly. This process however, is very intense and will demand all of the servers resources. I prefer to have some resources available at all times and don’t overload the CPUs.

basecalling

When the sequencing run has finished, the raw signal in fast5 files needs to be converted to fastq files with nucleotide information. This process is called basecalling, and our mpp-server is not well equiped for this process. Frankly, a CPU is not well equiped for this process, but a GPU is. The mpp-server does not have a GPU recent enough to support the basecalling process, so I do this at my home computer. Just contact me and I’ll happily basecall them for you.

At home, I use a recent guppy basecaller installed in my home directory, and the “super accurate basecalling model”. The basecaller runs on a GeForce RTX 2060 with 6GB ram memmory.

~/bin/ont-guppy/bin/guppy_basecaller \

-i <...input-folder-with-fast5-files...> \

-s <...output-folder...> \

--compress_fastq \

-x "cuda:0" \

-c ~/bin/ont-guppy/data/dna_r9.4.1_450bps_sup.cfg \

--gpu_runners_per_device 8 \

--num_callers 8 \

--chunk_size 700 \

--chunks_per_runner 512 \

--trim_primers \

--trim_adapters \

--do_read_splitting

When working with a barcoded library, I do demultiplexing while basecalling by adding these two lines

--barcode_kits EXP-NBD104 \

--trim_barcodes

guppy optimisation yielded hardly any improvement

For the sake of efficiency, I did a few runs to see if guppy basecalling could be optimised.

Theoreticall, parameters can be calculated with the formula runners * chunks_per_runner * chunk_size < 100000 * [max GPU memory in GB]

However, I found I can easily go over that without any penalty but also not big improvements.

I did a couple of test runs with a single fast5 file straight out of minknow.

When choosing parameters that were to high, I would get an error that not enough memmory could be allocated.

In all other cases, memmory use did not go over 71% of the GPU.

PICe bandwith usage was always about 80 to 84%, and GPU usage between 95 and 99%.

| Setting | run1 | run2 | run3 | run4 | run5 | run6 | run7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| runners_per_device | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| chunk_size | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 500 | 700 | 1000 |

| chunks_per_runner | 410 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 512 | 512 | 256 |

| time (ms) | 129916 | 131365 | 136841 | 130577 | 133349 | 127237 | 129606 |

| time (min) | 2.17 | 2.19 | 2.28 | 2.18 | 2.22 | 2.12 | 2.16 |

| GPU mem (%) | 69 | 71 | 60 | 61 | 59 | 59 | 59 |

| theoretical ram (GB) | 8.2 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20.48 | 28.672 | 5.12 |

All in all, using a GPU for basecalling is an enormous improvement over CPU basecalling. But further than that, I can’t seem to optimise the process furter, at least not on my consumer grade hardware.

Assembly

When doing a first assembly, flye will do great.

It’s very fast, and in my experience does a very good job.

When optimising, perhaps canu is also worth a try.

Both are installed in a conda environment, activate on the mpp-server like so

conda activate /opt/miniconda/miniconda3/envs/canu

Alternativelly, see this conda environment.

subsampling reads

Often I sequence whole (meta)genome DNA extractions, even though I’m not interested in host DNA. For assembly of a specific organism, or exclusion of a specific organism, I map reads to a reference. In both cases, I have used minimap with an index I made as complete as possible. In other words, all organisms I might expect in my dna extraction, are in that file.

minimap2 <...minimap2-index...> \

<...nanopore-sequencing.fastq.gz...> \

-t 12 -a \

| samtools view -@ 6 -b \

> <...output.bamfile.bam...>

Then sort and index the bamfile with a tool of your choice (for example samtools sort and samtools index).

From this sorted bamfile, we can select or discard reads mapping to your contigs of interest with samtools view.

Such a command could look like this:

samtools view -h <...your.bamfile...> '<...your.region...>' \

| samtools fastq \

| nice pigz --best -p $(nproc) \

> <...yourselection.fastq.gz...>

In the command above we

- select hits from a bam file mapping to a specific region

- extract the reads as fastq

- compress the fasta file with pigz

- write the fasta hits to a file

trimming and QC

I have been very happy with the build-in trimming in the basecalling profile by nanopore.

nanopore only assembly

flye

A standard flye assembly commandline would like this. Flye has given us very good results in the past, and hence it is my go-to solution for nanopore assembly these days.

flye --nano-raw /stor/sequencing_files/<...yourfastq...>.fastq.gz \

--genome-size <genomesize like 6M or 48K or 7G> \

--threads $(nproc) \

--out-dir ~/<...your output directory...>

I recommend using all threads available like written above (provided these are not in use by someone else) and I recommend to write to the ssd.

Your home directories are on the SSD, and there’s also a /fast directory you could use to temporarily write stuff to.

Just make sure you move your assembly to /stor afterwards, so we keep the SSD clean for everyone.

canu

This command is usually my starting point for assembling with canu.

canu -assemble -nanopore-raw <...nanopore_sup.fastq.gz...> \

-d <...output_directory...> \

-p <...output_prefix...> \

genomeSize=<similar as for flye>

optionally, add parameters like so:

ErrorRate=0.1 \

-minReadLength=8000 \

-minOverlapLength=4000 \

Hybrid assembly

My tool of preference is SPAdes. A command to assemble Illumina first, then solve ambiguities in the graph with nanopore data looks like this: Parameters are tuned for our mpp server

spades -t 12 \

-m 60 \

-temp-dir /fast/spades \

--pe1-1 Illumina_library1.R1.fastq.gz \

--pe1-2 Illumina_library1.R2.fastq.gz \

--pe2-1 Illumina_library2.R1.fastq.gz \

--pe2-2 Illumina_library2.R2.fastq.gz \

--nanopore your_nanopore_reads.fasta \

-o SPAdes_assembly_hybrid_spades

Assembly visualisation

The obvious answer to this would be to map the original reads with the likes of blasr or minimap2 and then visualising the result in IGV or Tablet.

Additionally, I like to visualise the assembly graph in Bandage.

For a canu assembly, make sure the Bandage conda environment is activated and then execute in a terminal Bandage load ./path/to/assemblyprefix.contigs.gfa.

If you assembled reads from a clonal DNA extraction, or you fished out specific reads before, you may just get a circular contig with plasmid or two:

Scripting

Working with data and commandlines can make our lives a lot easier, and our science more reproducible. Here for example, I share a little script that I use to assemble several genomes I sequenced. A more elaborate version of this script is available on GitHub

#!/bin/bash

# This script takes FastQ data from the anabaena sequencing folder and assembles it with flye

# and might do other stuff in the future

# define where stuff is:

basedir=<your working directory for these analyses>

fqdir=<the directory containing the fastq.gz files you want to process>

# get an array of our samples directly from the available sequencing files

samples=( $(find "$fqdir" -maxdepth 1 -name '*.fastq.gz' -printf '%P\n') )

# make denovo assembly dir if it doesn't exist yet

if [ ! -d "$basedir"/denovo ]

then mkdir "$basedir"/denovo

fi

# for each sample, check if it is assembled already. If not, then assemble with flye

for s in "${samples[@]}"

do name=$(echo "$s" | sed 's/\.fastq\.gz//g' )

if [ ! -d "$basedir"/denovo/"$name" ]

then if [ ! $(command -v flye) ]

then echo 'flye is not found'

exit

fi

# assemble with flye with a max assembly coverage of 40, see flye manual for details

flye --nano-hq "$fqdir/$s" \

--genome-size 5M \

--threads $(nproc) \

--asm-coverage 40 \

--scaffold \

--out-dir "$basedir"/denovo/"$name"

fi

done

Assembly polishing

Polishing is achieved inside of flye already, and with about 40x coverage worked extremely well in data I worked with. I have used medaka for polishing too. Although medaka is made to work on pre-polished assemblies by racon, I often skip that step as also suggested in the nanopore website protocols.

synteny

mummer -> circos

mauve

Mauve is nice and visual, but can be a bit of a pain to run. I managed in the end like so: I created a conda environment to install Mauve from the bioconda repository. Unfortunaly, Mauve didn’t work still, but then I downloaded Mauve from the Darling lab website and installed it according to their instructions. Only when running the downloaded version of Mauve, inside the activated Mauve conda environment, did it run propperly. A bit cumbersome… but it works.

annotatioan of prokaryotic genomes

prokka

For annotation with prokka, I use a code like below. Prokka annotation has worked well the past years, but the software can be a bit of a pain to install. See this conda environment for my instalation specs.

prokka --outdir <...output.dir...> \

--addgenes \

--prefix <...custom.name...> \

--kingdom 'Bacteria' \

--cpus 0 \

--rfam \

<...input.fasta...>

bakta

For comparison, I typically also annotate with bakta. Bakta needs its own conda environment, specified here Code typically looks something like this:

First, amrfinderplus must be setup in the BaktaDB directory.

Assuming that directory is setup in some place defined by variable $baktaDB,

I include this code in my script to make sure it’s propperly installed:

if [ ! -d "$baktaDB"/amrfinderplus-db ]

then echo 'amrfinderplus-db is not setup correctly, doing that now'

amrdinamrfinder_update --database "$baktaDB"/amrfinderplus-db

fi

Then, we move on and use bakta to annotate a genome.

Only use the --complete option if chromosomes/plasmids are actually complete.

bakta --output <...output.dir...> \

--db "$baktaDB" \

--prefix <...custom.name...> \

--complete \

--threads $(nproc) \

<...input.fasta...>

ncbi pipeline

I’m quite satisfied with both prokka and bakta. However, the one thing they don’t do as of now, is annotate pseudogenes. The ncbi annotation pipeline does do that! More details on this later.

Variant calling

For variant calling with nanopore data we aim to have at the very least 40x coverage, but ideally a lot more.

In my previous work, I searched for long IN/DEL variations, depending on your definition perhaps structural variations.

To this end, I have used two methods.

For SNPs and IN/DELs or smaller structural variations, I used medaka like below.

Make sure to change the model -m if appropriate.

medaka_haploid_variant -i <...your.fastqgz...> \

-r <...your.reference.fasta> \

-o <...your.output.dir...> \

-t $(nproc) \

-m r941_min_sup_variant_g507

Software details are available in this [conda environement].

Large structural variations, we looked for with sniffles and read mapper ngmlr. These large structural variations were confirmed in a de-novo assembly as well. Sniffles requires ngmlr mapped bam files:

ngmlr -q <...your.fastqgz...> \

-r <...your.reference.fasta> \

--rg-sm <...sample.name...> \

-t $(nproc) \

-x ont \

-o <...output.sam...>

#adapt sam performance parameters if required:

samtools sort -@ 6 -m 9G \

<...ngmlr.samfile.sam...> \

| samtools view -b -@ 6 -h \

> <...output.sorted.bam...>

samtools index <...ngmlr.sorted.bam...>

rm "<...output.sam...>

Variant calling is done like so:

sniffles --input <...ngmlr.sorted.bam...> \

--reference <...your.reference.fasta> \

--snf <...output.snf...> \

--vcf <...output.vcf...>

Finally, a multi-sample vcf can be made like so:

sniffles --input <..all.snf.files...> --vcf <...your.multi-sample.vcf...>

A more elaborate example is available here.